Women’s hearts give silent warnings

Women’s heart health: Gaps in diagnosis and declining awareness

Mira’s case illustrates where care can be improved:

The statements by the patient described herein are based on results that were achieved in this specific patient case. Since there is no "typical" patient case and many variables exist there can be no guarantee that other patients achieve the same results.

The statements by customers of Siemens Healthineers described herein are based on results that were achieved in the customer's unique setting. Because there is no “typical” hospital or laboratory and many variables exist (e.g., hospital size, samples mix, case mix, level of IT and/or automation adoption) there can be no guarantee that other customers will achieve the same results.

[1] Cushman M, Shay CM, Howard VJ, Jiménez MC, Lewey J, McSweeney JC, et al. Ten-year differences in women’s awareness related to coronary heart disease: Results of the 2019 American heart association national survey: A special report from the American heart association. Circulation [Internet]. 2021;143(7). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000000907

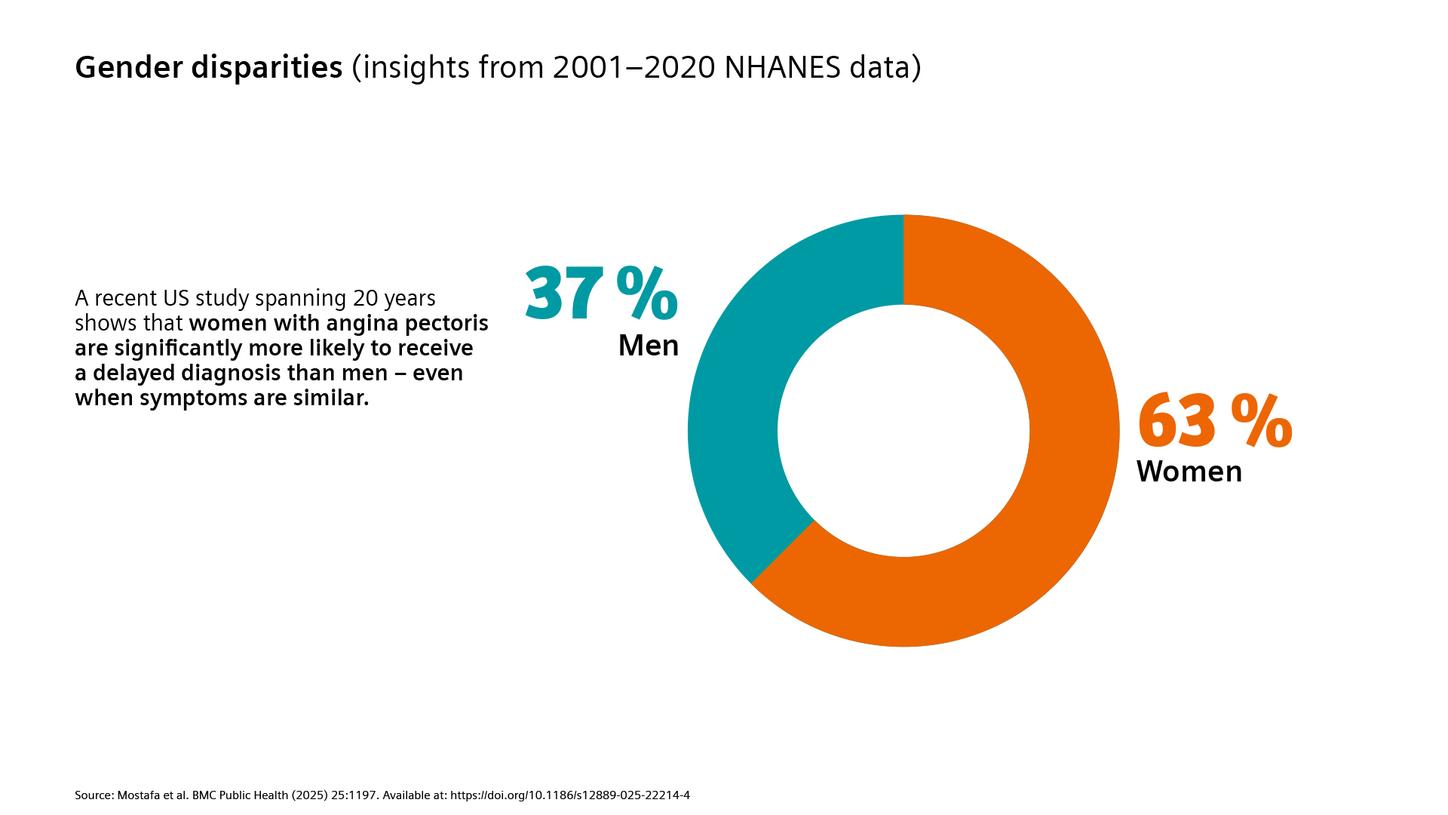

[2] Mostafa N, Sayed A, Hamed M, Dervis M, Almaadawy O, Baqal O. Gender disparities in delayed angina diagnosis: insights from 2001–2020 NHANES data. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2025;25(1). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-22214-4

[3] Cushman M, Shay CM, Howard VJ, Jiménez MC, Lewey J, McSweeney JC, et al. Ten-year differences in women’s awareness related to coronary heart disease: Results of the 2019 American heart association national survey: A special report from the American heart association. Circulation [Internet]. 2021;143(7). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000000907

[4] Canto JG, Rogers WJ, Goldberg RJ, Peterson ED, Wenger NK, Vaccarino V, et al. Association of age and sex with myocardial infarction symptom presentation and in-hospital mortality. JAMA [Internet]. 2012;307(8). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.199

[5] Canto JG. Symptom presentation of women with acute coronary syndromes: Myth vs reality. Arch Intern Med [Internet]. 2007;167(22):2405. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archinte.167.22.2405

[6] Galbraith M, Drossart I. Disparity in diagnosis and treatment of cardiovascular disease in women: a call to joint action from the European Society of Cardiology Patient Forum. Eur Heart J [Internet]. 2024;45(2):79–80. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad480

[7] Escardio.org. [cited 2026 Feb 5]. Available from: https://www.escardio.org/Councils/Council-for-Cardiology-Practice-(CCP)/Cardiopractice/acute-coronary-syndrome-in-women

Oup.com. [cited 2026 Feb 5]. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/45/2/79/7243236

Decision support tools [Internet]. Escardio.org. [cited 2026 Feb 5]. Available from: https://www.escardio.org/education/resources/decision-support-tools/

[8] Mostafa N, Sayed A, Hamed M, Dervis M, Almaadawy O, Baqal O. Gender disparities in delayed angina diagnosis: insights from 2001-2020 NHANES data. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2025;25(1):1197. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-22214-4

[9] Galbraith M, Drossart I. on behalf of the ESC Patient Forum. Disparity in diagnosis and treatment of cardiovascular disease in women: a call to joint action from the ESC Patient Forum. European Heart Journal [Internet]. 2024;45:79–80. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad480

[10] Kunadian V, Chieffo A, Camici PG. An EAPCI Expert Consensus Document on Ischaemia With Non Obstructive Coronary Arteries (INOCA). European Heart Journal [Internet]. 2020;41:3504–20. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa503

[11] Acute coronary syndrome in women [Internet]. Escardio.org. [cited 2026 Feb 5]. Available from: https://www.escardio.org/Councils/Council-for-Cardiology-Practice-(CCP)/Cardiopractice/acute-coronary-syndrome-in-women

Paradies V, Masiero G, Rubboli A, Van Beusekom HMM, Costa F, Capranzano P, et al. Antithrombotic drugs for acute coronary syndromes in women: sex-adjusted treatment and female representation in randomised clinical trials. A clinical consensus statement of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) and the ESC Working Group on Thrombosis. Eur Heart J [Internet]. 2025;46(28):2730–41. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaf352

[12] Giordano V, Mercuri C, Simeone S. Behavioral delays in seeking care among post acute myocardial infarction women: a qualitative study following PCI. Frontiers in Global Women’s Health [Internet]. 2025;6. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fgwh.2025.1501237

[13] Canto JG, Rogers WJ, Goldberg RJ, Peterson ED, Wenger NK, Vaccarino V, et al. Association of age and sex with myocardial infarction symptom presentation and in-hospital mortality. JAMA [Internet]. 2012;307(8). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.199

[14] Canto JG. Symptom presentation of women with acute coronary syndromes: Myth vs reality. Arch Intern Med [Internet]. 2007;167(22):2405. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archinte.167.22.2405

[15] Acute coronary syndrome in women [Internet]. Escardio.org. [cited 2026 Feb 5]. Available from: https://www.escardio.org/Councils/Council-for-Cardiology-Practice-(CCP)/Cardiopractice/acute-coronary-syndrome-in-women

[16] Canto JG, Rogers WJ, Goldberg RJ, Peterson ED, Wenger NK, Vaccarino V, et al. Association of age and sex with myocardial infarction symptom presentation and in-hospital mortality. JAMA [Internet]. 2012;307(8). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.199

[17] Mostafa N, Sayed A, Hamed M, Dervis M, Almaadawy O, Baqal O. Gender disparities in delayed angina diagnosis: insights from 2001-2020 NHANES data. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2025;25(1):1197. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-22214-4

[18] Kunadian V, Chieffo A, Camici PG. An EAPCI Expert Consensus Document on Ischaemia With Non Obstructive Coronary Arteries (INOCA). European Heart Journal [Internet]. 2020;41:3504–20. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa503

[19] Kunadian V, Chieffo A, Camici PG. An EAPCI Expert Consensus Document on Ischaemia With Non Obstructive Coronary Arteries (INOCA). European Heart Journal [Internet]. 2020;41:3504–20. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa503

[20] Galbraith M, Drossart I. on behalf of the ESC Patient Forum. Disparity in diagnosis and treatment of cardiovascular disease in women: a call to joint action from the ESC Patient Forum. European Heart Journal [Internet]. 2024;45:79–80. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad480

[21] Mostafa N, Sayed A, Hamed M, Dervis M, Almaadawy O, Baqal O. Gender disparities in delayed angina diagnosis: insights from 2001-2020 NHANES data. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2025;25(1):1197. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-22214-4

[22] Maas AHEM, Rosano G, Cifkova R, Chieffo A, van Dijken D, Hamoda H, et al. Cardiovascular health after menopause transition, pregnancy disorders, and other gynaecologic conditions: a consensus document from European cardiologists, gynaecologists, and endocrinologists. Eur Heart J [Internet]. 2021;42(10):967–84. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa1044