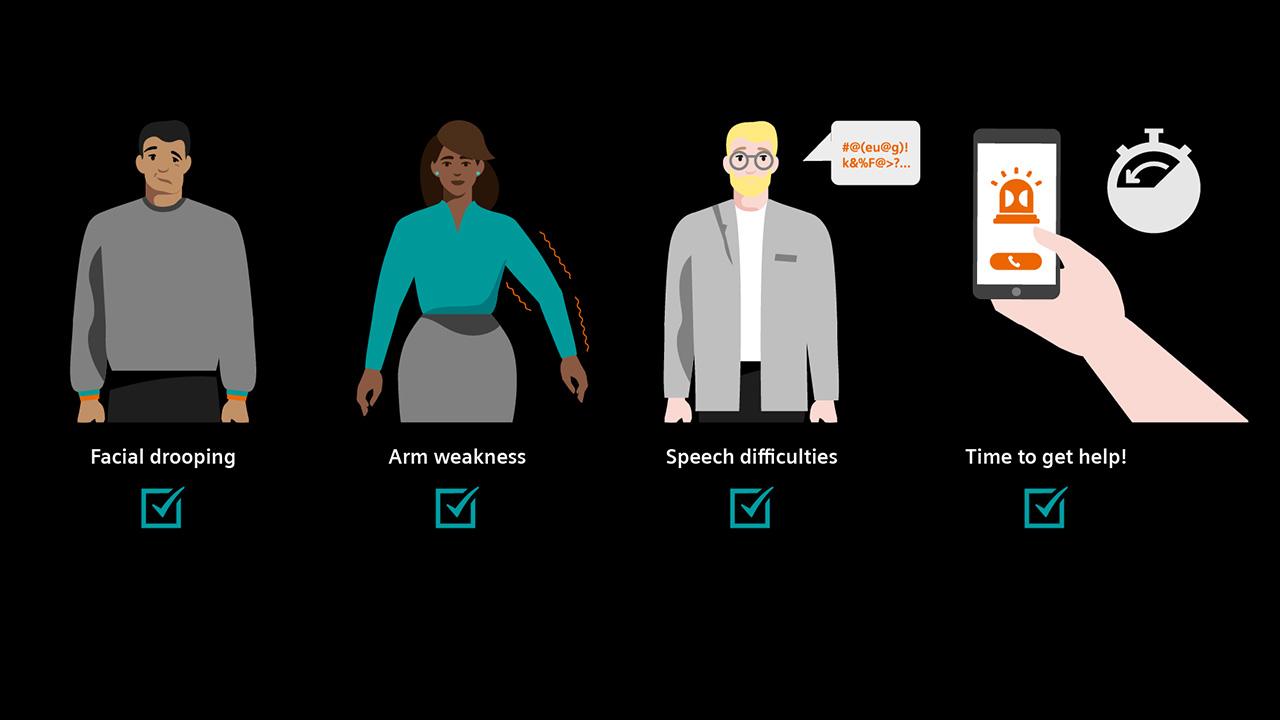

Reducing the toll through greater awareness

Strokes are rare in children. But when they strike, they can be devastating. Awareness and quick action can save lives and prevent lifelong disability.

I’m very grateful to be alive.

Zosia Wasylewski

[1] “Management of Stroke in Neonates and Children: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association,” Stroke, March 2019. Accessed online 04/13/2022: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/STR.0000000000000183

[2] “Pediatric Strokes,” Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, accessed online 02/13/2022 https://www.chop.edu/conditions-diseases/pediatric-stroke

[3] “A Faster Way to Treat Strokes in Kids,” Atrium Health, accessed online 14/13/2022 https://atriumhealth.org/dailydose/2022/01/14/A-Faster-Way-to-Treat-Strokes-in-Kids?utm_source=twitter&utm_campaign=organic_social

[4] “Pediatric Stroke: Overview and Recent Updates,” Aging and Disease, Volume 12, Number 4; 1043-1055, July 2021 Full text available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8219494/pdf/ad-12-4-1043.pdf

[5] “Pediatric Stroke Causes and Recovery,” American Stroke Association, accessed online 04/13/2022: https://www.stroke.org/en/about-stroke/stroke-in-children/pediatric-stroke-causes

[6] “Pediatric Stroke Infograph,” American Stroke Association, accessed online 04/13/2022: https://www.stroke.org/en/about-stroke/stroke-in-children/pediatric-stroke-infographic

[7] “A Family Guide to Pediatric Stroke,” Heart & Stroke Foundation, Canada, accessed online 04/13/2022: https://heartstrokeprod.azureedge.net/-/media/pdf-files/canada/other/a-family-guide-to-pediatric-stroke-eng.ashx?la=en&rev=5f193826693e4acfbc149e9dc9fbc24e