A quarter of a century ago, the world’s first commercial PET/CT scanner was developed. Although initially met with uncertainty, the medical community vigorously embraced the modality as an indispensable diagnostic imaging tool and one that can provide life-saving information for countless patients, even for one of the scanner’s inventors.

How it all began

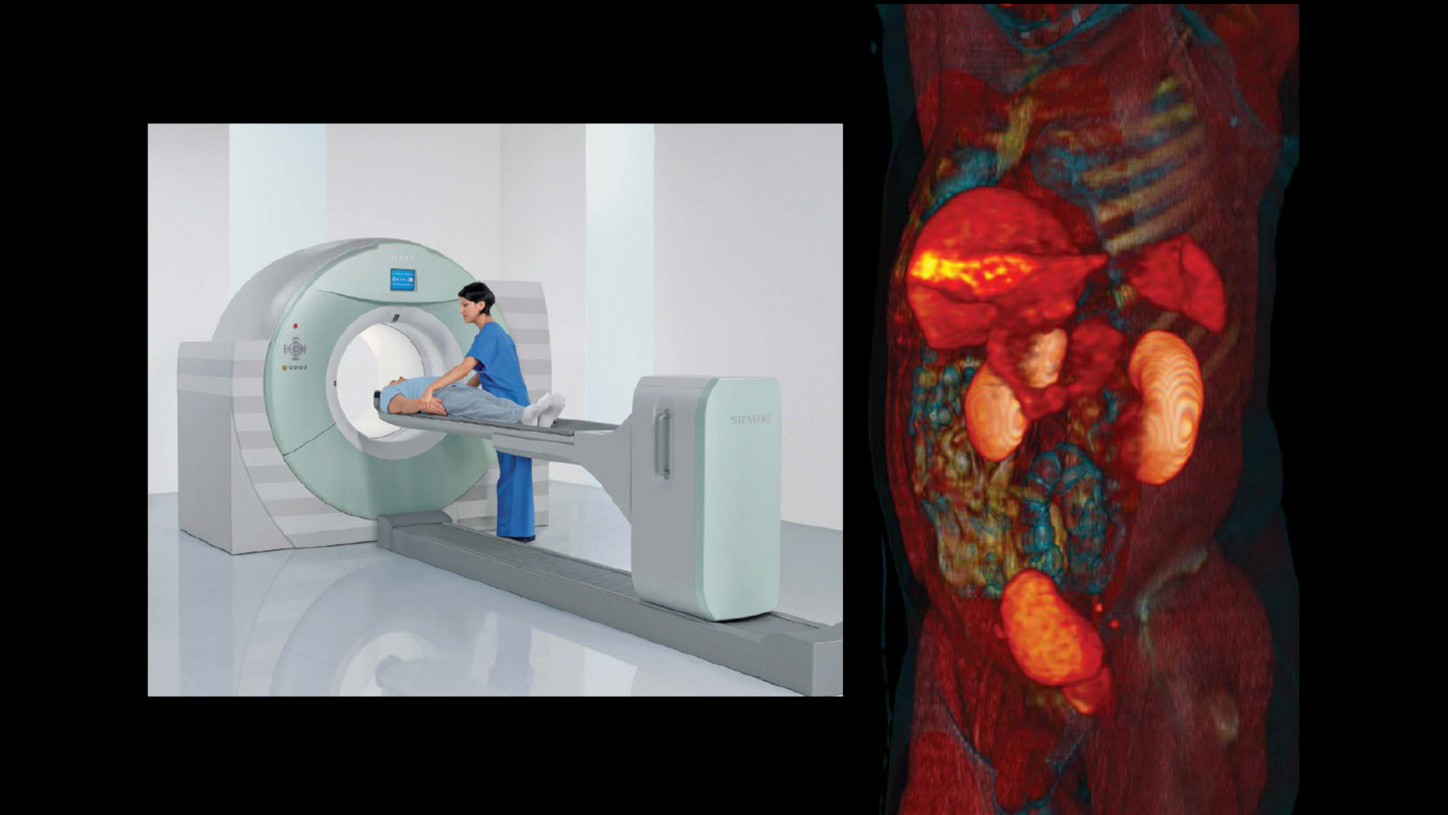

Time flies. Looking back, David Townsend, PhD, can hardly believe it has been twenty-five years since he and his team, based at the University of Pittsburgh, developed the device in collaboration with Ronald Nutt, PhD, CEO of CTI PET Systems, in Knoxville, Tennessee, USA. Since then, numerous innovations have propelled PET/CT to even higher and wider applications.

The story of PET/CT begins in the early 1970s in Geneva, Switzerland, almost 30 years before the first PET/CT scanner was developed. Back then, Townsend joined the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN), the European particle physics laboratory. At the time, PET was far from being a clinical tool—it was a research project with uncertain applications. Townsend started looking at potential detector applications for PET in 1975 along with Alan Jeavons, PhD.

Click on each year to explore the timeline

Four years later, Townsend moved to University of Geneva Hospital to focus entirely on PET scanner development. In 1988, while working at University of Geneva Hospital, Townsend collaborated with CTI PET Systems and Terry Jones, DSc, from Hammersmith Hospital, London, UK, to design and build a cost-effective, rotating PET scanner based on the BGO (bismuth germanium oxide) block detectors developed by CTI PET Systems. Townsend and Jones‘s rotating prototype scanner imaged patients at the University of Geneva Hospital and was later commercialized by CTI PET Systems as the Advanced Rotating Scanner (ART) that represented a cost-effective PET scanner.

2000

Biograph is the first commercial PET/CT system installed at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA. This system is revolutionary in that it combines PET and CT in a single diagnostic system. TIME magazine hails the PET/CT as “Medical Invention of the Year.”1

The birth of PET/CT

How did the idea of combining PET and CT come about? As with many groundbreaking innovations, it started with a simple question—and a bit of chance.

According to Townsend, an oncology

surgeon at the University of Geneva

Hospital walked by the PET scanner

one day and wondered if it would be

possible to add CT to the scanner

design. His reasoning was practical:

PET, at the time, was mostly confined

to research centers, while every

physician was familiar with CT.

Townsend considered that idea.

“So, I called Nutt at CTI and asked

him, ‘How about adding CT to PET?’” Townsend recalls. “For us, as scientists

and engineers, it made sense.

You’re combining complementary

information—the high-resolution

anatomical detail of CT with the

functional imaging of PET—and

offering physicians both in a single

device. While some degree of

alignment of two separate CT and PET

scans could be achieved using software,

this approach was really only effective

and reliable for brain imaging.”

Fast forward to 1995 at the

University of Pittsburgh. Townsend,

along with physicist Thomas Beyer,

PhD, MBA, and bioengineer Paul

Kinahan, PhD, teamed up with Nutt

to turn their concept into reality,

funded by the National Cancer

Institute (NCI). In close partnership,

CTI contributed the PET technology,

while Siemens provided the CT

components. The team was also

backed by the Department of

Radiology at the University of

Pittsburgh, where Townsend worked.

The prototype PET/CT was built at

the CTI factory in Knoxville and then

moved to the PET facility at the

University of Pittsburgh to start

clinical scanning. Within three years,

they had developed a prototype and

began acquiring the first-ever clinical

PET/CT images of patients.

2008

Biograph mCT is announced as the world’s first molecular computed tomography system and represents the evolution of integration in imaging. Biograph mCT is a combination of a state-of-the-art CT scanner with a high-performance PET system.

A modality looking for a home

At the 1998 Society of Nuclear Medicine (SNM) annual meeting in Toronto, Canada, Townsend shared the first clinical PET/CT images with the world. Townsend looks back, “It was a very exciting time to be to be involved in nuclear medicine.” CTI and Siemens did not begin looking at the commercialization of PET/CT until about 1999, after enough clinical image data was acquired to convince physicians that it was a useful clinical concept.

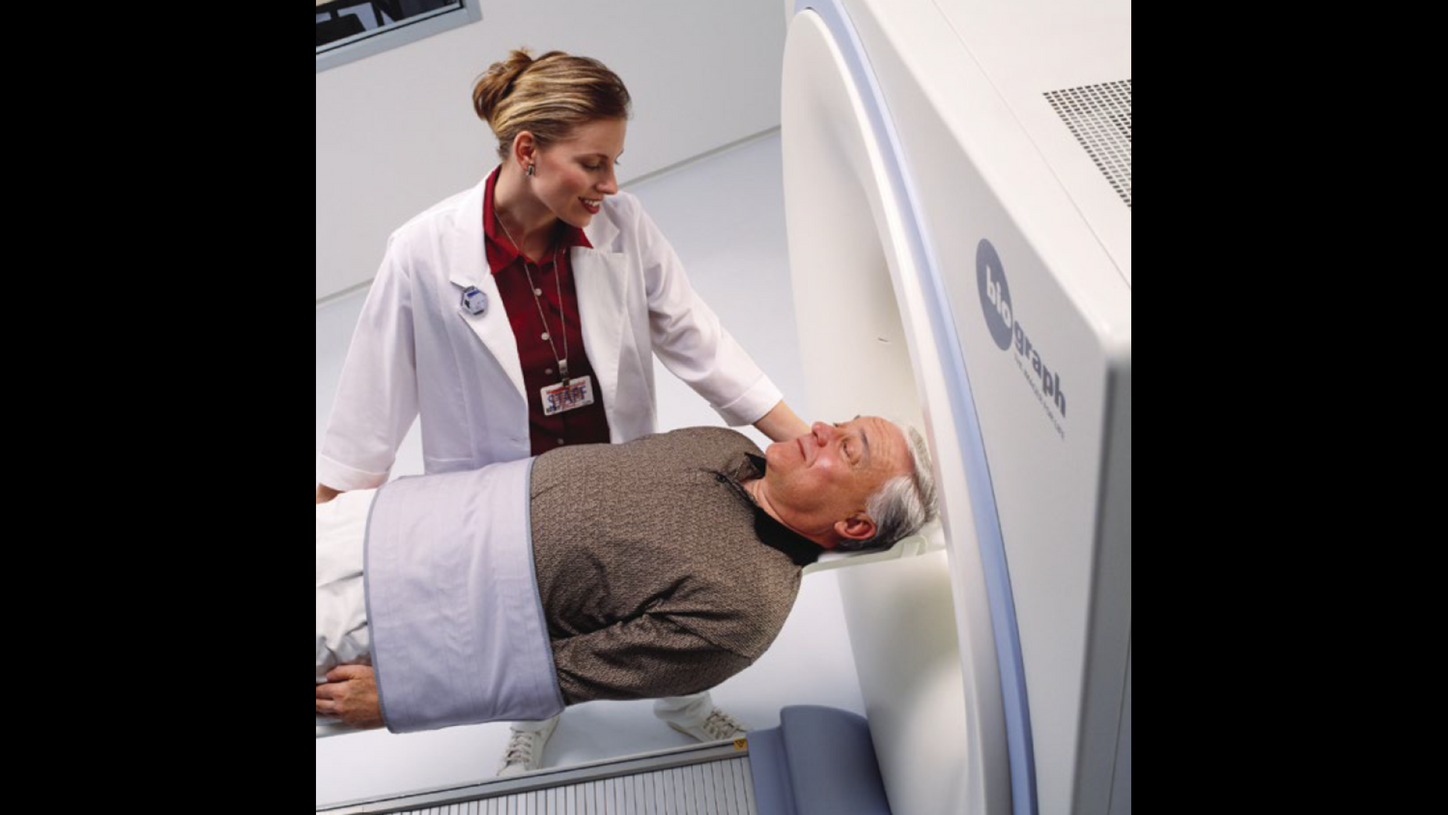

While surgeons and oncologists were generally more receptive to the idea, the wider medical community’s initial reaction to the new PET/CT scanner was, at best, uncertain. Why? Because it was hybrid technology that did not quite fit. Was it nuclear medicine? Was it radiology? No one knew exactly where it belonged. And would it require two technologists to operate it? Two physicians to read the scans? Many questions were asked.

The co-inventors, Townsend and Nutt, and members of the team remained involved in PET/CT’s development. In November 2000, the new scanner was unveiled to the world at the Radiological Society of North America’s (RSNA) annual meeting in Chicago, Illinois, USA. In December of the same year, the PET/ CT concept and prototype design was honored by TIME magazine as “Medical Invention of the Year.”1 By mid-2001, the first commercially available Siemens Biograph PET/CT system was installed at the University of Pittsburgh.

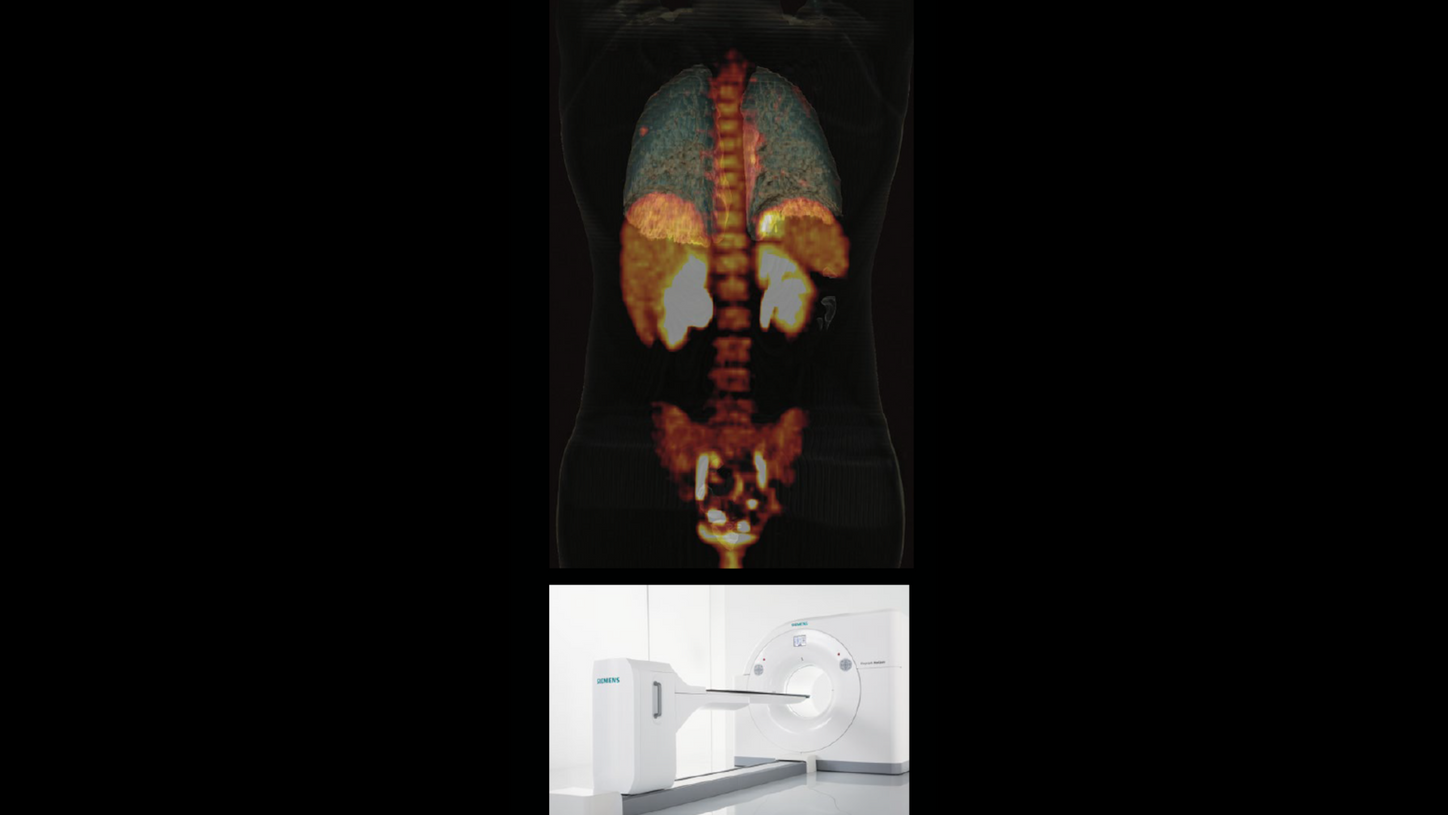

2013

Biograph mCT Flow is the first PET/CT system to move the patient through the gantry while continuously acquiring PET data.

“’How about adding CT to PET?’…For us, as scientists and engineers, it made sense. You’re combining complementary information—the high-resolution anatomical detail of CT with the functional imaging of PET—and offering physicians both in a single device.”

2015

Biograph Horizon offers high-resolution imaging, advanced PET and CT technologies, and AI-powered workflows. Its compact design and simplified operations enable more healthcare providers to offer a higher standard of care to more patients.

Pushing PET/CT forward with ground-breaking innovation

Since PET/CT’s unveiling at RSNA, the modality’s capabilities continue to expand. Maurizio Conti, PhD, joined the Siemens molecular imaging team in 2000. Today, he serves as director of PET Physics and Reconstruction at Siemens Healthineers in Knoxville. When asked about the biggest technological developments in PET/CT over the past 25 years, he quickly points to two key milestones: replacing BGO detector blocks with lutetium oxyorthosilicate (LSO) scintillators, which enabled time-of-flight (TOF) imaging, and the later introduction of silicon photomultipliers (SiPMs), which dramatically improved time resolution. These two breakthroughs significantly elevated image quality and greatly accelerated the scanning time, which in turn helped increase patient comfort.

Conti also speaks with particular pride about two projects: the first TOF PET/CT scanner from Siemens Healthineers, Biograph mCT, which was “a revolution in those years—a truly outstanding machine,” he says— and Biograph Vision Quadra total-body PET/CT. “It was an unusually fast project. Can you believe that it was done in about 1.5 years?”

In the last 25 years, software

development has also played a critical

role. Advances in reconstruction and

data correction have greatly improved

image quality, especially for how

attenuation correction and image noise

are handled in obese patients. TOF

reconstruction now helps compensate for patient size and even motion—from

breathing to heartbeats.

“Using different tracers, and more specific tracers, we can understand not only what a disease is, but if it’s aggressive or not. And that correlates with the organs and the anatomy, which only PET/CT can do.”

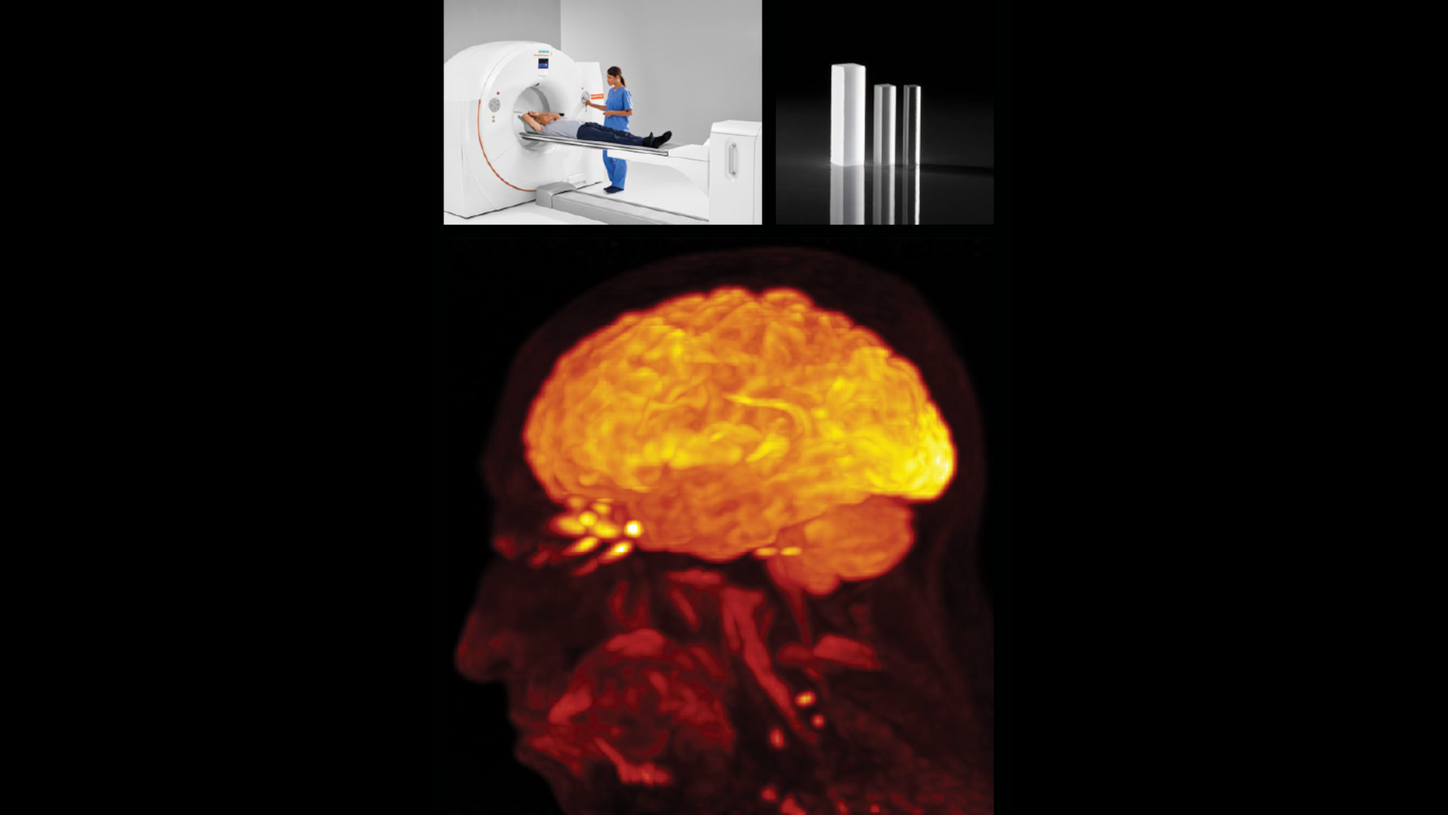

2017

Biograph Vision PET/CT is launched with an innovative design that reduces the size of the detector’s crystal elements from 4 x 4 mm to 3.2 x 3.2 mm and generates 214-picosecondtrue TOF performance that leverages the full potential of SiPM technology.

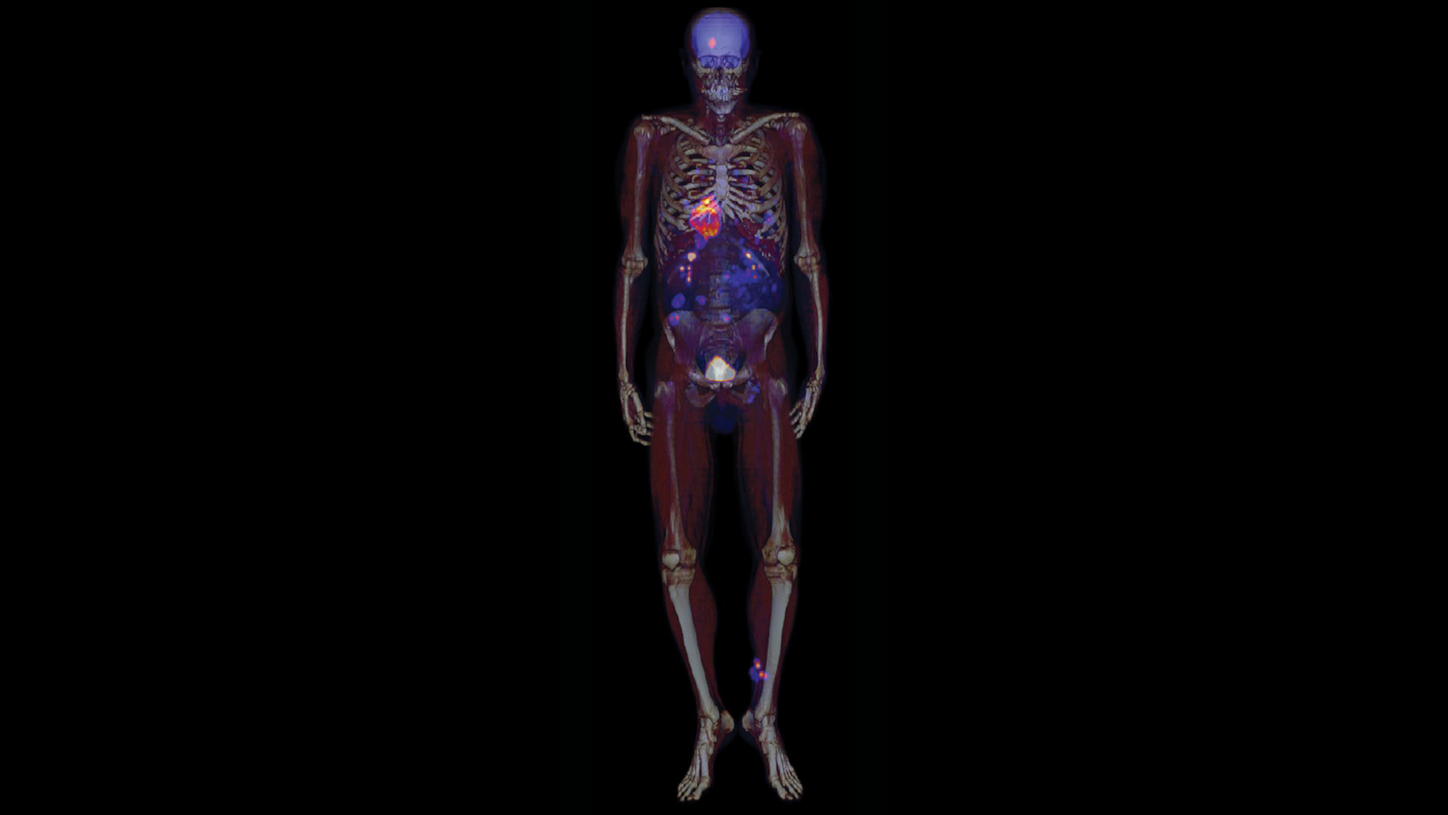

Reflecting on the progress over

the past 25 years, Townsend says

“Nowadays, you have very powerful

instruments compared to what we

had in 2000. And they provide superb,

unbelievable imaging capabilities in

times we didn’t even dream of back in

those days. The development of total body

imaging with large field-of-view

systems is now a reality. We used to

work with 15-cm axial extent, and now

you have a system like Biograph Vision

Quadra, which has 106-cm axial field

of view (aFOV). You can look at

dynamics between different organs,

which we could never do, and that’s

been a tremendous step forward.

Because you know we would image

either the brain or the heart or the liver,

maybe the lungs, lower abdomen—

but the body is a total system.”

Ability to understand disease and improve treatment

The defining strength of PET/CT remains its ability to combine functionality and anatomy in a single scan. But there is even more to it today. “Using different tracers, and more specific tracers, we can understand not only what a disease is, but if it’s aggressive or not. And that correlates with the organs and the anatomy, which only PET/CT can do,” Conti explains.

It all started with the generic tracer fludeoxyglucose injection F 18 (FDG) to measure metabolism. But now, a growing number of novel tracers are available, providing deeper insight into disease function that comes with PET. “This is a great future,” says Conti. “Today, we have access to highly specific tracers such as PSMA for prostate cancer, tau and amyloid for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease evaluation, and rubidium for cardiac imaging. As the spectrum tracers broadens, so does the potential for earlier, more accurate disease detection and improved treatment monitoring.”

Full circle: from pioneer to patient

Last year, Townsend himself

underwent a PET/CT scan following

the discovery of a suspicious nodule

in his left lung. The PET/CT was

consistent with an adenocarcinoma

that was confirmed by biopsy.

Fortunately, it was an early stage 1

tumor that was removed surgically

and a 6-month follow-up scan showed

no evidence of disease. Reflecting on

his own patient experience, Townsend

recalled that the imaging team who

performed the scan at the University

of British Columbia Cancer Centre,

Vancouver, Canada, were aware of

Townsend‘s background. The

technologist who gave him the

injection of FDG quipped, “‘I guess I

don’t need to explain the imaging

procedure to you, do I?‘” remembers

Townsend, with a smile.

2020

Biograph Vision Quadra takes its place as the first 106-cm aFOV whole-body scanner with ultra-high sensitivity, for advanced research, clinical flexibility, and improved patient outcomes. The scanner fits traditional PET/CT spaces while enabling dynamic, multi-organ, and low-dose imaging.

What may the next 25 years bring?

When asked about the next developments in PET/CT, Conti envisions a future full of potential—from widespread use of artificial intelligence to more advanced motion correction, improved speed and image quality, and increased patient comfort. Theranostics and opportunities for more personalized therapy are also on the horizon.

And what are his personal hopes for the next 25 years of PET/CT? Conti pauses, then offers two wishes: “More tracers that unlock the full potential of our amazing technology. And that PET/CT becomes more accessible to patients earlier in the care pathway. Right now, a patient needs to have a cancer diagnosis to maybe get a PET/CT scan. I would love a world where PET/CT is routine, where patients receive a PET/CT when there is suspicion of cancer.” As for Townsend? His wish echoes a similar sentiment: that PET/CT technology is widely available to all patients no matter where they live.

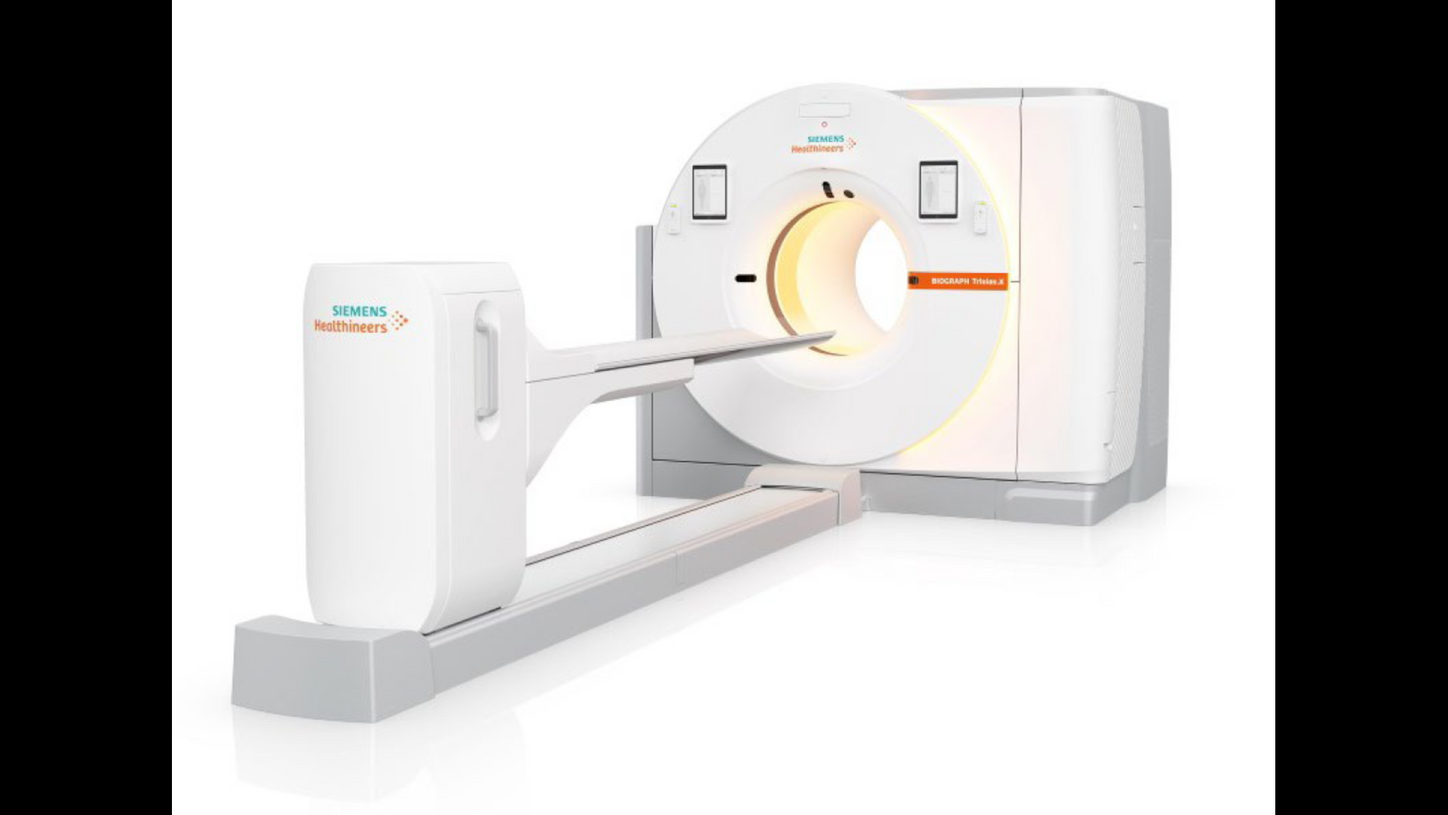

2025

Biograph Trinion.X meets evolving clinical demands with greater speed, sensitivity, and a patient-focused design. The system’s ultra-fast 197-picosecond time-of-flighta capability is a key advancement, along with an extended aFOV of up to 48 cm.

The defining strength of PET/CT remains its ability to combine functionality and anatomy in a single scan. With the use of more specific tracers, PET/CT can provide deeper insights into diseases, their aggressiveness, and their correlation with organs and anatomy. Paving the way for earlier, more accurate detection and improved treatment monitoring and working toward making PET/CT accessible to all patients is an ambition shared by clinicians and researchers alike.

PET/CT served as catalyst for other hybrids of nuclear medicine with anatomical measures, such as in PET/MR. The success of PET/CT commercially encouraged the industry to develop and market other hybrids. The audacity of PET/CT was daunting; its success equally so. The next 25 years will undoubtedly hold more exciting developments.

Fludeoxyglucose F 18

Please see Indications and Important Safety Information for Fludeoxyglucose F 18 (18F FDG) Injection.